Getting Started with Athlytics

Athlytics Package

2026-02-20

Source:vignettes/athlytics_introduction.Rmd

athlytics_introduction.RmdWelcome to Athlytics

This tutorial will guide you through a complete workflow—from loading your Strava data to generating training analytics. By the end, you’ll understand how to use all core features of Athlytics for longitudinal exercise physiology analysis.

What You’ll Learn:

- How to load and explore your Strava export data

- Calculate and interpret training load metrics (ACWR)

- Analyze aerobic fitness trends (Efficiency Factor)

- Quantify cardiovascular drift (Decoupling)

- Track personal bests and performance progression

- Export results for further analysis

Time Required: 30-60 minutes

Prerequisites

Installation

For installation instructions, see the README. The quick version:

# CRAN (stable)

install.packages("Athlytics")

# GitHub (latest features)

remotes::install_github("HzaCode/Athlytics")Your Strava Data Export

You’ll need a Strava data export ZIP file. If you haven’t exported your data yet, start from Strava and follow the steps in the README Quick Start.

Quick Summary: 1. Set Strava language to

English first: Strava Settings → Display Preferences → Language

→ English. The CSV export uses localized column headers, so non-English

exports will fail to parse correctly. 2. Go to Strava Settings → My

Account → Download or Delete Your Account 3. Request “Download” (NOT

delete!) 4. Wait for email with download link 5. Download the ZIP file

(e.g., export_12345678.zip) 6. Don’t unzip

it — Athlytics reads ZIP files directly

Loading Your Data

Understanding the Data Structure

Let’s explore what we just loaded:

# How many activities do you have?

nrow(activities)

# Example output: [1] 847

# What sports are in your data?

table(activities$type)

# Example output:

# Ride Run Swim

# 312 498 37

# Date range

range(activities$date, na.rm = TRUE)

# Example output: [1] "2018-01-05" "2024-12-20"

# Key columns in the dataset

names(activities)Important Columns:

-

id— Unique activity identifier -

date— Activity date -

type— Activity type (Run, Ride, Swim, etc.) -

distance— Distance in kilometers -

moving_time— Moving time in seconds -

average_heartrate— Average heart rate (if recorded) -

max_heartrate— Maximum heart rate -

average_speed— Average speed (m/s) -

average_watts— Average power for cycling (if available) -

elevation_gain— Total elevation gain (meters)

Data Quality Checks

Before analysis, it’s good practice to check your data:

# Summary statistics

summary(activities |> select(distance, moving_time, average_heartrate))

# Check for missing heart rate data

sum(!is.na(activities$average_heartrate)) / nrow(activities) * 100

# Shows % of activities with HR data

# Activities without HR data

activities |>

filter(is.na(average_heartrate)) |>

count(type)Pro Tip: Many Athlytics functions require heart rate

data. Filter for !is.na(average_heartrate) when calculating

EF or decoupling.

Filtering Your Data

For focused analysis, you’ll often want to filter by type or date:

# Only running activities

runs <- activities |>

filter(type == "Run")

# Recent activities (last 6 months)

recent <- activities |>

filter(date >= Sys.Date() - 180)

# Runs with heart rate data from 2024

runs_2024_hr <- activities |>

filter(

type == "Run",

!is.na(average_heartrate),

lubridate::year(date) == 2024

)

# Long runs only (> 15 km)

long_runs <- activities |>

filter(type == "Run", distance > 15)Core Analyses

Now let’s dive into the main analytical features. Each metric provides different insights into your training and physiology.

1. Training Load (ACWR)

What is ACWR?

The Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) compares your recent training (acute load, typically 7 days) to your long-term baseline (chronic load, typically 28 days). It helps you monitor whether you are ramping up training too quickly.

Basic ACWR Calculation

# Calculate ACWR for all running activities

acwr_data <- calculate_acwr(

activities_data = runs,

activity_type = "Run", # Filter by activity type

load_metric = "duration_mins", # Can also be "distance_km" or "hrss"

acute_period = 7, # 7-day rolling average

chronic_period = 28 # 28-day rolling average

)

# View results

head(acwr_data)Output Columns:

-

date— Date -

atl— Acute Training Load (7-day rolling average) -

ctl— Chronic Training Load (28-day rolling average) -

acwr— Raw ACWR ratio (ATL / CTL) -

acwr_smooth— Smoothed ACWR (rolling mean ofacwr)

Visualizing ACWR

# Basic plot

plot_acwr(acwr_data)

# With risk zones highlighted (recommended)

plot_acwr(acwr_data, highlight_zones = TRUE)Demo with Sample Data:

# Load built-in sample data

data("sample_acwr", package = "Athlytics")

# Plot ACWR with risk zones

plot_acwr(sample_acwr, highlight_zones = TRUE)

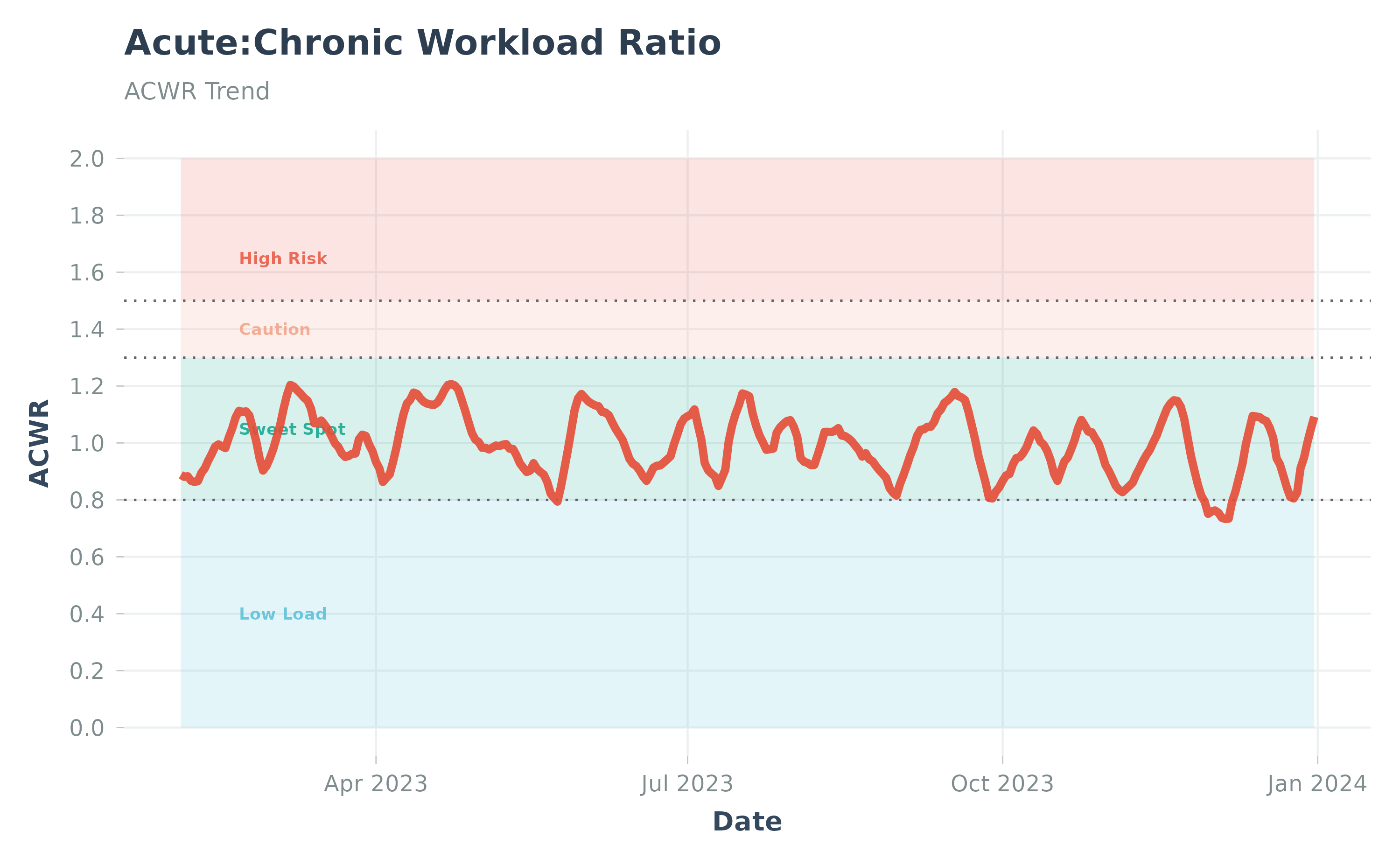

ACWR visualization using sample data

Risk Zones

- < 0.8 — Undertraining (fitness may decline)

- 0.8-1.3 — “Sweet spot” (optimal adaptation zone)

- 1.3-1.5 — Moderate risk (load increasing rapidly)

- > 1.5 — High risk (excessive load spike, injury risk)

Interpreting Your ACWR

What to look for:

- Gradual increases = Good progressive overload

- Sharp spikes above 1.5 = Warning signs, consider recovery

- Extended periods < 0.8 = May need to increase training volume

- Stable values in 0.8-1.3 = Optimal training stimulus

Practical Example:

Choosing Load Metrics

Different load metrics for different goals:

-

duration_mins— Simple, works for all sports, good for general monitoring -

distance_km— Better for distance-focused training (marathon prep) -

hrss— Most accurate for physiological load (requires HR data)

Note on terminology: When using

duration_minsordistance_km, you are technically measuring training volume rather than true physiological load. True training load accounts for intensity (e.g., heart rate, power). For more accurate load estimation, usehrsswhich incorporates heart rate data. This distinction is important: two athletes could have the same duration-based ACWR but very different physiological stress if their intensities differ. For research applications, always prefer intensity-weighted metrics (e.g., HRSS, TRIMP) over simple volume measures.See: Impellizzeri, F. M., et al. (2020). Training load and its role in injury prevention, part I: Back to the future. Journal of Athletic Training, 55(9), 885-892. DOI: 10.4085/1062-6050-500-19; Foster, C. (1998). Monitoring training in athletes with reference to overtraining syndrome. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 30(7), 1164-1168. DOI: 10.1097/00005768-199807000-00023

# Calculate using HRSS (heart rate stress score)

acwr_hrss <- calculate_acwr(

activities_data = runs,

load_metric = "hrss" # Automatically calculated if average_heartrate available

)Important Caveats

ACWR is widely used in practice, but its interpretation — especially as an “injury risk” indicator — is debated in the sports science literature. The original framework was proposed by Hulin et al. (2014) and popularized by Gabbett (2016), but subsequent analyses have questioned its predictive validity (Impellizzeri et al., 2020; Lolli et al., 2019), and a further critique called for dismissing the ACWR framework entirely (Impellizzeri et al., 2021). Use risk zones as descriptive heuristics rather than validated injury predictors.

Key references:

- Gabbett, T. J. (2016). The training-injury prevention paradox. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(5), 273-280. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788

- Hulin, B. T., et al. (2014). Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(8), 708-712. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092524

- Lolli, L., et al. (2019). The acute-to-chronic workload ratio: An inaccurate scaling index for an unnecessary normalisation process? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(24), 1510-1512. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098884

- Impellizzeri, F. M., et al. (2020). Acute:chronic workload ratio: Conceptual issues and fundamental pitfalls. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 15(6), 907-913. DOI: 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0864

- Impellizzeri, F. M., et al. (2021). What role do chronic workloads play in the acute to chronic workload ratio? Time to dismiss ACWR and its underlying theory. Sports Medicine, 51(3), 581-592. DOI: 10.1007/s40279-020-01378-6

2. Efficiency Factor (EF)

What is EF?

Efficiency Factor measures how much output (speed/power) you generate per unit of input (heart rate). It’s a key indicator of aerobic fitness improvements.

Metrics:

- speed_hr (running) — Speed (m/s) / HR: Higher values = faster at same HR = better aerobic fitness

- gap_hr (running on hilly terrain) — Grade Adjusted Speed (m/s) / HR: Accounts for elevation changes using Strava’s GAP data. Recommended for hilly routes where raw speed doesn’t reflect true effort.

- power_hr (cycling) — Power (W) / HR: Higher values = more power at same HR = better aerobic fitness

Handling Elevation: For hilly runs, use

ef_metric = "gap_hr"to account for gradient. This uses Strava’s Grade Adjusted Pace (GAP) data, which represents the equivalent flat-ground speed (m/s) adjusted for terrain gradient, providing more accurate efficiency comparisons across varied terrain.

What Changes Mean:

- Increasing EF = Aerobic fitness improving (doing more work at same HR)

- Stable EF = Maintaining current fitness

- Decreasing EF = Fatigue, overtraining, or fitness loss

Calculate EF

# For running (Speed/HR)

ef_runs <- calculate_ef(

activities_data = runs,

activity_type = "Run",

ef_metric = "speed_hr" # Speed (m/s) / HR

)

# For cycling (Power/HR)

rides <- activities |> filter(type == "Ride")

ef_cycling <- calculate_ef(

activities_data = rides,

activity_type = "Ride",

ef_metric = "power_hr" # Power divided by HR

)

# View results

head(ef_runs)Output Columns:

-

date— Activity date -

activity_type— Activity type (Run, Ride, etc.) -

ef_value— Efficiency Factor value -

status— Calculation status (ok, no_streams, non_steady, etc.)

Visualizing EF Trends

# Basic plot

plot_ef(ef_runs)

# With smoothing line to see trend (recommended)

plot_ef(ef_runs, add_trend_line = TRUE)

# Smooth per activity type (separate trend lines for each discipline)

# Note: requires data with multiple activity types (e.g., Run + Ride)

ef_multi <- calculate_ef(activities_data = activities, ef_metric = "speed_hr")

plot_ef(ef_multi, add_trend_line = TRUE, smooth_per_activity_type = TRUE)Demo with Sample Data:

# Load built-in sample data (contains Run + Ride activities)

data("sample_ef", package = "Athlytics")

# Plot EF with trend line

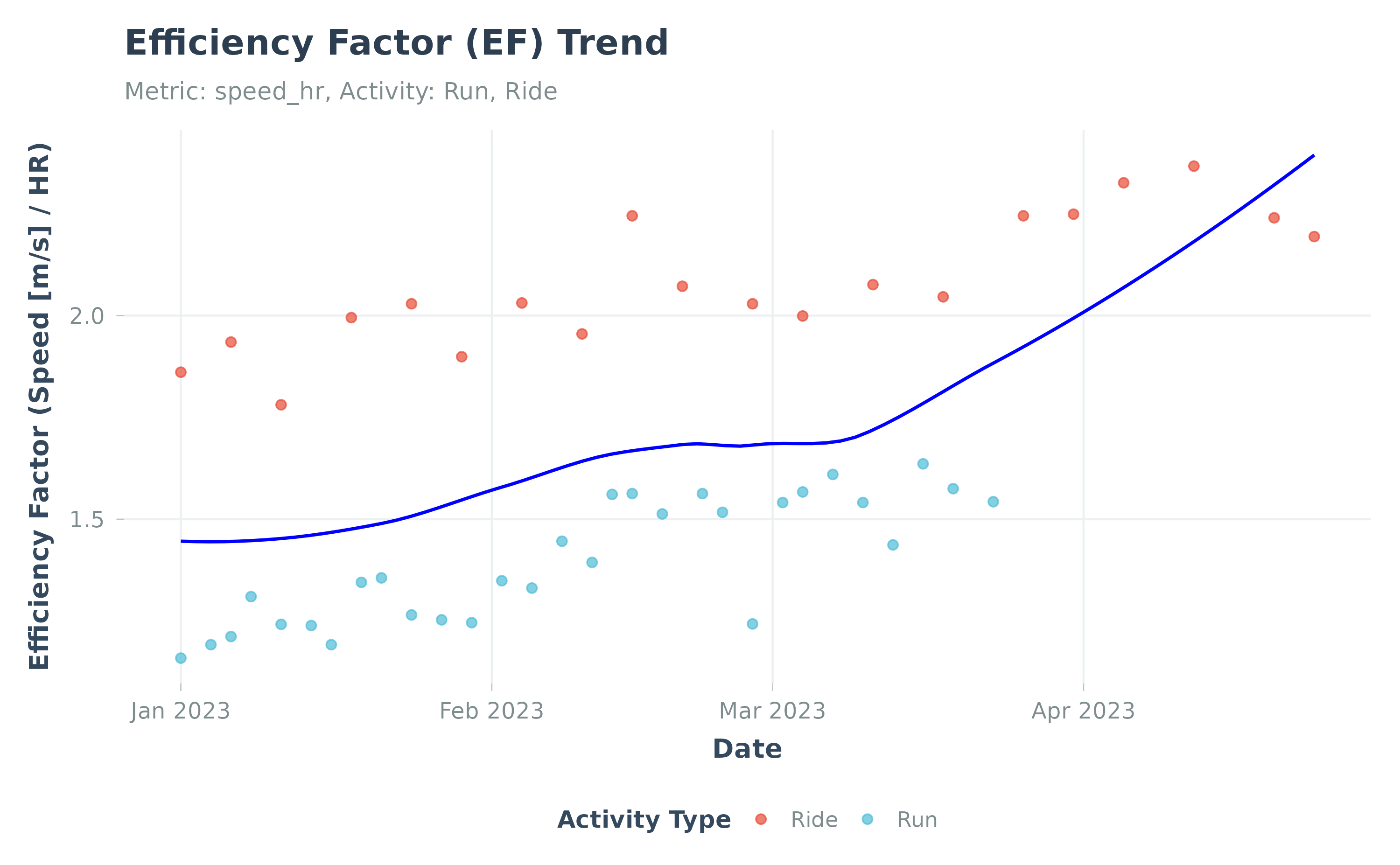

plot_ef(sample_ef, add_trend_line = TRUE)

#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

Efficiency Factor trend using sample data

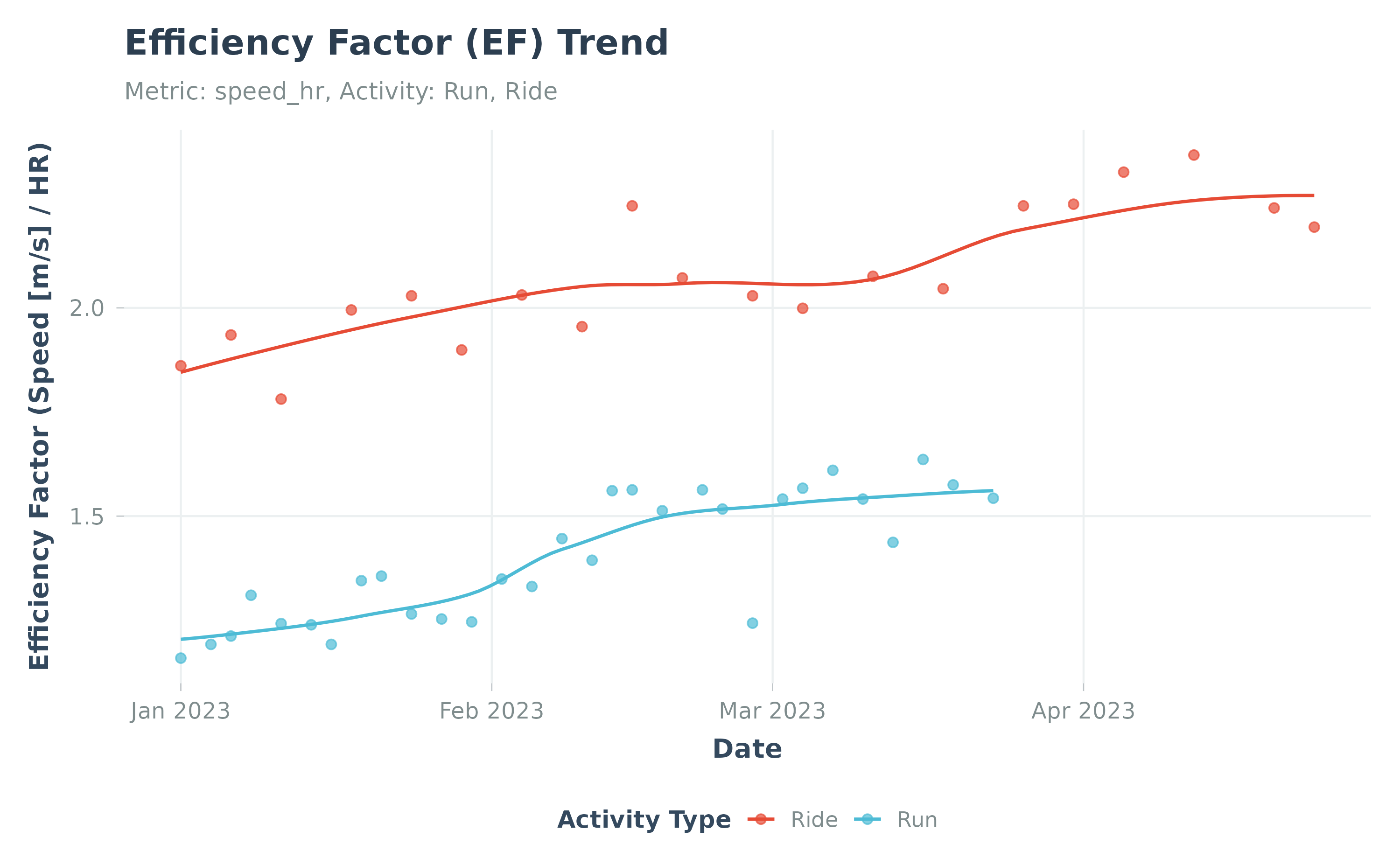

Demo: Separate trend lines per discipline:

# Smooth per activity type to compare trends across disciplines

plot_ef(sample_ef, add_trend_line = TRUE, smooth_per_activity_type = TRUE)

#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

EF with per-discipline smoothing

Interpreting EF

Best Practices:

- Track trends over weeks/months, not day-to-day fluctuations

- Use steady-state efforts only — Interval workouts will skew results. The package uses coefficient of variation (CV) thresholds to identify steady-state segments, a common approach in exercise physiology (Coyle & González-Alonso, 2001).

- Consider external factors — Heat, altitude, fatigue affect EF

Scientific Background: Steady-state exercise is characterized by relatively constant oxygen consumption and heart rate (CV < 8-10%). This package automatically filters non-steady activities to ensure EF calculations reflect true aerobic efficiency rather than pacing artifacts.

See: Coyle, E. F., & González-Alonso, J. (2001). Cardiovascular drift during prolonged exercise. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 29(2), 88-92. DOI: 10.1097/00003677-200104000-00009; Allen, H., Coggan, A. R., & McGregor, S. (2019). Training and Racing with a Power Meter (3rd ed.). VeloPress. ISBN: 978-1-937715-93-9

Technical Detail: Steady-State Detection Algorithm

- Rolling window: A centered rolling window of min(300, N/4) data points (minimum 60 points, ~1-5 minutes at 1 Hz sampling) is applied to the activity stream.

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): For each window position, CV = rolling SD / rolling mean is calculated for the primary metric (velocity for running, power for cycling).

-

Filtering: Data points where CV <

steady_cv_threshold(default 8%) are classified as steady-state segments. -

Minimum duration: For EF, at least 100 steady-state

data points are required. For decoupling, the steady-state segment must

span at least

min_steady_minutes(default 40 minutes). - Aggregation: EF and decoupling are computed from steady-state data only, using median-based aggregation to reduce sensitivity to outliers.

Practical Analysis:

# Calculate monthly average EF

library(lubridate)

ef_monthly <- ef_runs |>

mutate(month = floor_date(date, "month")) |>

group_by(month) |>

summarise(

mean_ef = mean(ef_value, na.rm = TRUE),

n_activities = n()

) |>

arrange(desc(month))

print(ef_monthly)

# Compare first vs last 3 months

recent_ef <- ef_runs |>

filter(date >= Sys.Date() - 90) |>

pull(ef_value)

baseline_ef <- ef_runs |>

filter(date < Sys.Date() - 90, date >= Sys.Date() - 180) |>

pull(ef_value)

cat(sprintf(

"Recent EF: %.2f\nBaseline EF: %.2f\nChange: %.1f%%\n",

mean(recent_ef, na.rm = TRUE),

mean(baseline_ef, na.rm = TRUE),

(mean(recent_ef, na.rm = TRUE) / mean(baseline_ef, na.rm = TRUE) - 1) * 100

))3. Cardiovascular Decoupling

While EF tracks aerobic efficiency across activities over time, decoupling looks within a single activity to measure how efficiency changes from start to finish.

What is Decoupling?

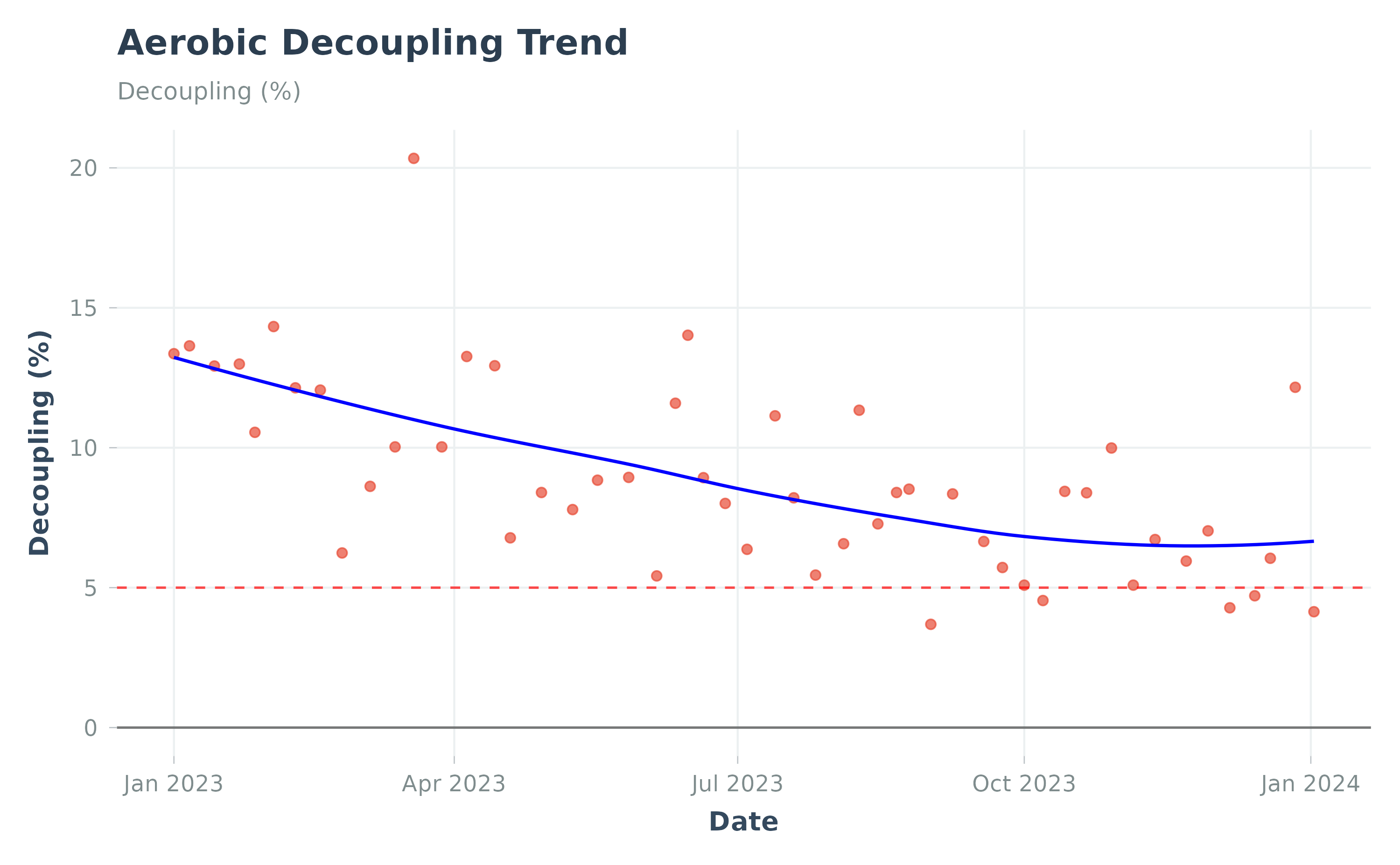

Decoupling quantifies cardiovascular drift—the phenomenon where heart rate gradually rises during prolonged efforts even if pace/power remains constant. Low decoupling indicates good aerobic endurance.

How It Works:

The function compares efficiency (speed/HR or power/HR) between the first half and second half of an activity:

Positive values = efficiency decline in second half (HR drift); <5% commonly used as reference threshold, requires interpretation in context of steady-state and environmental conditions (Coyle & González-Alonso, 2001; Friel, 2009).

Interpretation:

- < 5% — Excellent aerobic base, well-adapted

- 5-10% — Acceptable, some drift but manageable

- > 10% — Significant drift (fatigue, heat, insufficient base fitness)

Calculate Decoupling

# For running

decoupling_runs <- calculate_decoupling(

activities_data = runs,

activity_type = "Run",

decouple_metric = "speed_hr",

min_duration_mins = 60 # Only analyze runs ≥ 60 minutes

)

# For cycling

decoupling_rides <- calculate_decoupling(

activities_data = rides,

activity_type = "Ride",

decouple_metric = "power_hr",

min_duration_mins = 90 # Longer threshold for cycling

)

# View results

head(decoupling_runs)Output Columns:

-

date— Activity date -

decoupling— Decoupling percentage (%). Positive = HR drift -

status— Calculation status (ok, non_steady, insufficient_data)

Visualizing Decoupling

# Basic plot

plot_decoupling(data = decoupling_runs)

# With trend line

plot_decoupling(data = decoupling_runs, add_trend_line = TRUE)Demo with Sample Data:

# Load built-in sample data

data("sample_decoupling", package = "Athlytics")

# Plot decoupling trend

plot_decoupling(data = sample_decoupling)

#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

Cardiovascular decoupling using sample data

Practical Applications

1. Assess Aerobic Base:

# Recent decoupling average

recent_decouple <- decoupling_runs |>

filter(date >= Sys.Date() - 60) |>

summarise(avg_decouple = mean(decoupling, na.rm = TRUE))

if (recent_decouple$avg_decouple < 5) {

cat("Excellent aerobic base! Ready for higher intensity.\n")

} else if (recent_decouple$avg_decouple < 10) {

cat("Good base, continue building aerobic foundation.\n")

} else {

cat("High decoupling—focus on more easy, long runs.\n")

}2. Monitor Training Block Progress:

# Compare decoupling over time

library(ggplot2)

decoupling_runs |>

ggplot(aes(x = date, y = decoupling)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6) +

geom_smooth(method = "loess", se = TRUE) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 5, linetype = "dashed", color = "green") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 10, linetype = "dashed", color = "orange") +

labs(

title = "Decoupling Trend Over Time",

subtitle = "Lower values = better aerobic endurance",

x = "Date", y = "Decoupling (%)"

) +

theme_minimal()Important Note: Decoupling is highly affected by environmental conditions (heat, humidity) and cumulative fatigue. Always interpret in context. See: Friel, J. (2009). The Cyclist’s Training Bible (4th ed.). VeloPress — for practical application of decoupling in endurance training.

4. Personal Bests (PBs)

Track your best performances at standard distances over time. Systematic personal best tracking across multiple distances is a well-established method for monitoring endurance performance progression. Analyzing PBs at different distances helps distinguish between improvements in speed (shorter distances) and aerobic endurance (longer distances), aligning with periodization principles (Matveyev, 1981).

Calculate PBs

# Extract personal bests

pbs <- calculate_pbs(

activities_data = runs,

activity_type = "Run"

)

# View all PRs

print(pbs)Supported Distances:

- 400m, 800m, 1km, 1 mile

- 5km, 10km

- Half marathon, Marathon

Visualize PB Progression

# Plot PR progression

plot_pbs(pbs)

# Filter to specific distance

pbs_5k <- pbs |> filter(distance == "5k")

print(pbs_5k)Demo with Sample Data:

# Load built-in sample data

data("sample_pbs", package = "Athlytics")

# Plot PB progression

plot_pbs(data = sample_pbs)

#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

Personal bests progression using sample data

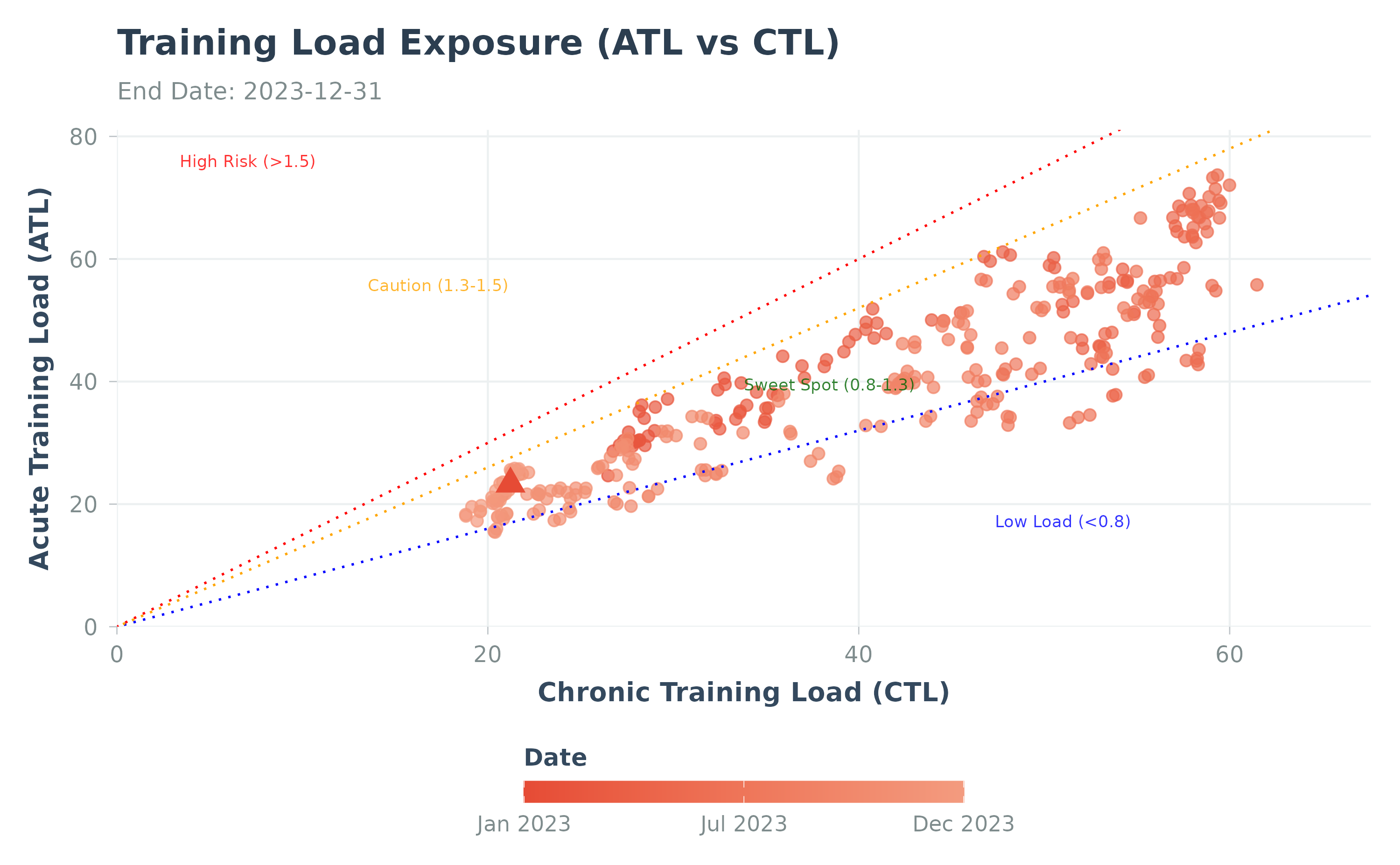

5. Load Exposure Analysis

Visualize your training state in 2D space: acute load vs chronic load.

How does this differ from ACWR? Both use the same underlying data (ATL and CTL), but provide different perspectives:

- ACWR collapses acute and chronic load into a single ratio plotted over time — it tells you when load spikes occurred.

- Load Exposure preserves the two-dimensional relationship (ATL vs CTL scatter plot) — it tells you where you are in the fitness-fatigue state space, revealing whether a high ACWR comes from ramping up on a low base (risky) or from a natural fluctuation on a high base (less risky).

In practice, use ACWR for day-to-day monitoring and Load Exposure for strategic planning across training phases. Using both together gives a more complete picture than either alone.

Calculate and Plot Exposure

# Calculate exposure

exposure <- calculate_exposure(

activities_data = runs,

activity_type = "Run",

load_metric = "duration_mins"

)

# Plot with risk zones

plot_exposure(data = exposure, risk_zones = TRUE)Demo with Sample Data:

# Load built-in sample data

data("sample_exposure", package = "Athlytics")

# Plot exposure

plot_exposure(data = sample_exposure)

#> Warning: Removed 27 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

#> (`geom_point()`).

Load exposure analysis using sample data

Interpretation:

- Points above diagonal = Acute > chronic (ramping up training)

- Points on diagonal = Balanced state

- Points below diagonal = Tapering or recovery

- Red zone = High ACWR, injury risk

Complete Workflow Example

Here’s a realistic, end-to-end analysis workflow:

library(Athlytics)

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

# ---- 1. Load and Filter Data ----

activities <- load_local_activities("my_strava_export.zip")

# Focus on running activities with HR data

runs <- activities |>

filter(type == "Run", !is.na(average_heartrate))

cat(sprintf("Loaded %d running activities with HR data\n", nrow(runs)))

# ---- 2. Training Load Monitoring ----

acwr_data <- calculate_acwr(

activities_data = runs,

load_metric = "duration_mins"

)

# Check current training status

current_acwr <- acwr_data |>

filter(date >= Sys.Date() - 30) |>

tail(1) |>

pull(acwr_smooth)

cat(sprintf("Current ACWR: %.2f\n", current_acwr))

# Visualize

p1 <- plot_acwr(acwr_data, highlight_zones = TRUE) +

labs(title = "6-Month Training Load Progression")

print(p1)

# ---- 3. Aerobic Fitness Tracking ----

ef_data <- calculate_ef(

activities_data = runs,

ef_metric = "speed_hr"

)

# Calculate fitness trend

ef_trend <- ef_data |>

mutate(month = lubridate::floor_date(date, "month")) |>

group_by(month) |>

summarise(mean_ef = mean(ef_value, na.rm = TRUE))

p2 <- plot_ef(ef_data, add_trend_line = TRUE) +

labs(title = "Aerobic Efficiency Trend")

print(p2)

# ---- 4. Endurance Assessment ----

# Only for long runs (> 60 min)

decoupling_data <- calculate_decoupling(

activities_data = runs,

min_duration_mins = 60

)

avg_decouple <- mean(decoupling_data$decoupling, na.rm = TRUE)

cat(sprintf(

"Average decoupling: %.1f%% (%s aerobic base)\n",

avg_decouple,

ifelse(avg_decouple < 5, "excellent",

ifelse(avg_decouple < 10, "good", "needs work")

)

))

p3 <- plot_decoupling(data = decoupling_data) +

labs(title = "Cardiovascular Drift in Long Runs")

print(p3)

# ---- 5. Export Results ----

# Save plots

ggsave("acwr_analysis.png", plot = p1, width = 10, height = 6, dpi = 300)

ggsave("ef_trend.png", plot = p2, width = 10, height = 6, dpi = 300)

ggsave("decoupling.png", plot = p3, width = 10, height = 6, dpi = 300)

# Export data for further analysis

write.csv(acwr_data, "acwr_results.csv", row.names = FALSE)

write.csv(ef_data, "ef_results.csv", row.names = FALSE)

write.csv(decoupling_data, "decoupling_results.csv", row.names = FALSE)

cat("\nAnalysis complete! Results saved.\n")Troubleshooting

Common Issues

“No data returned” or empty results

Causes: - Activity type filter doesn’t match your data - Required metrics (e.g., HR) are missing - Date range has no activities

Solutions:

# Check activity types in your data

table(activities$type)

# Check for HR data availability

sum(!is.na(activities$average_heartrate))

# Verify date range

range(activities$date, na.rm = TRUE)

# Try without filtering first

test <- calculate_acwr(activities_data = activities, activity_type = NULL)“Not enough data for chronic period”

ACWR requires at least 28 days of data. Check your date range:

# How much data do you have?

date_span <- as.numeric(max(activities$date) - min(activities$date))

cat(sprintf("Your data spans %d days\n", date_span))

# If < 28 days, you need more data or use shorter periods“NA values in output”

Some activities may lack required metrics (HR, power, etc.):

# Filter before calculating

runs_with_hr <- runs |> filter(!is.na(average_heartrate))

ef_data <- calculate_ef(runs_with_hr, ef_metric = "speed_hr")Getting Help

-

Function documentation:

?calculate_acwr,?plot_ef, etc. - GitHub Issues: Report bugs

-

Package vignettes:

browseVignettes("Athlytics")

Next Steps

Congratulations! You now know how to use all core features of Athlytics.

Advanced Features

Ready to go deeper? Check out:

- Advanced Features Tutorial — EWMA-based ACWR with confidence intervals, quality control, and cohort analysis

- Function Reference — Complete documentation of all functions

For Researchers

If you’re using Athlytics for research:

- Cohort Studies: See calculate_cohort_reference() for multi-athlete percentile comparisons

- Data Quality: Use flag_quality() for stream data quality control

- Statistical Analysis: All functions return tidy data frames ready for lme4, survival analysis, etc.

Session Info

sessionInfo()

#> R version 4.5.2 (2025-10-31)

#> Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

#> Running under: Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS

#>

#> Matrix products: default

#> BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libblas.so.3

#> LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libopenblasp-r0.3.26.so; LAPACK version 3.12.0

#>

#> locale:

#> [1] LC_CTYPE=C.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=C.UTF-8

#> [4] LC_COLLATE=C.UTF-8 LC_MONETARY=C.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=C.UTF-8

#> [7] LC_PAPER=C.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C LC_ADDRESS=C

#> [10] LC_TELEPHONE=C LC_MEASUREMENT=C.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

#>

#> time zone: UTC

#> tzcode source: system (glibc)

#>

#> attached base packages:

#> [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

#>

#> other attached packages:

#> [1] ggplot2_4.0.2 Athlytics_1.0.4

#>

#> loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

#> [1] Matrix_1.7-4 gtable_0.3.6 jsonlite_2.0.0 dplyr_1.2.0

#> [5] compiler_4.5.2 tidyselect_1.2.1 jquerylib_0.1.4 splines_4.5.2

#> [9] systemfonts_1.3.1 scales_1.4.0 textshaping_1.0.4 yaml_2.3.12

#> [13] fastmap_1.2.0 lattice_0.22-7 R6_2.6.1 labeling_0.4.3

#> [17] generics_0.1.4 knitr_1.51 htmlwidgets_1.6.4 tibble_3.3.1

#> [21] desc_1.4.3 lubridate_1.9.5 bslib_0.10.0 pillar_1.11.1

#> [25] RColorBrewer_1.1-3 rlang_1.1.7 cachem_1.1.0 xfun_0.56

#> [29] fs_1.6.6 sass_0.4.10 S7_0.2.1 otel_0.2.0

#> [33] timechange_0.4.0 cli_3.6.5 mgcv_1.9-3 withr_3.0.2

#> [37] pkgdown_2.2.0 magrittr_2.0.4 digest_0.6.39 grid_4.5.2

#> [41] nlme_3.1-168 lifecycle_1.0.5 vctrs_0.7.1 evaluate_1.0.5

#> [45] glue_1.8.0 farver_2.1.2 ragg_1.5.0 rmarkdown_2.30

#> [49] tools_4.5.2 pkgconfig_2.0.3 htmltools_0.5.9